When most people think about what determines the price of a particular commodity such as gold or crude oil, they only consider supply and demand economics. This is after all what we’re most familiar with: when summer comes around and the weather warms up, we get into our car more often and go for a drive or a longer road trip. Since we use more gas during the summer months, demand is up. Gas stations respond by jacking up the price of gasoline.

Another example many of us are familiar with takes place during the cold winter months. To heat our homes, we use more energy, using commodities such as natural gas or heating oil. Since we use more of them for heating purposes, this increases demand and, you guessed it, drives up the price for those commodities during the winter season. If you look at long term charts for energy commodities, it becomes clear that prices follow this cyclical pattern with seasonal spikes.

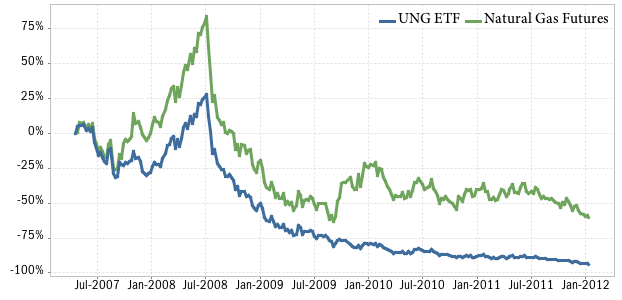

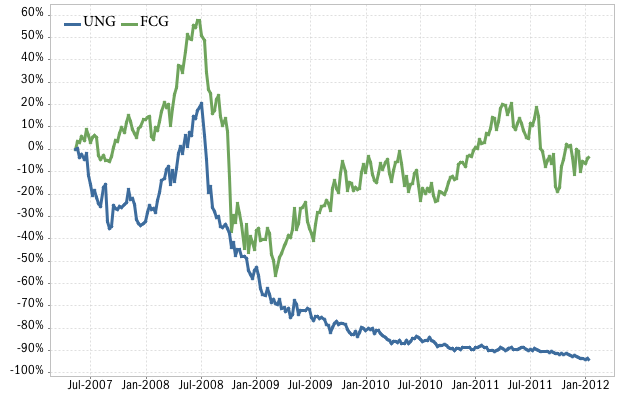

But commodity prices don’t always follow a predictable pattern, because changes in supply and demand often are independent. For example, several years ago, oil and gas exploration companies developed the hydraulic fracturing technology required to extract shale gas. Gas production soared, and the increase in supply has driven natural gas prices (including those of natural gas ETFs) to ten year lows.

A fair market price is set based on supply and demand for the commodity. Or as Karl Marx once put it: “From the taste of wheat it is not possible to tell who produced it, a Russian serf, a French peasant or an English capitalist.” And so the price of wheat for two equivalent bushels should be the same.

But in addition to the supply/demand equilibrium, there is another important factor at play: speculation. Take for example gold. Sure, there is high demand for the metal in electronics and other industries, as a currency reserve, and for other reasons. But there are also a lot of investors who are simply attracted to the rising price of gold, and want to “get in on some of that action.”

There are now over 70 billion U.S. dollars invested in the most widely held gold ETF. That means that through this one exchange traded security, investors now own more gold bullion than the reserve bank of most large nations such as China, Russia, Switzerland, or Japan!

Popularity feeds on itself. The financial media are out in force, advertising gold ETFs in newspapers, magazines, and on TV shows. If that’s not speculation, I don’t know what is.

Another example of a speculative run-up in commodities was when hedge fund managers (and others) in 2007-2008 loaded up on commodities, fueling a massive increase in their prices. When they all exited in mass during the next year (as the global economic crisis unfolded) the prices of many commodities plummeted, and have still not recovered to this date. Commodities are not the only market that exhibits speculative behavior. We’ve seen it in stocks (think Nasdaq dot-coms in the late 1990s), real estate, tulip bulbs, you name it.

In summary, the price of commodities is determined not just by fundamental reasons, but also speculation by various participants in this dynamic market. Sometimes the speculative return component drives commodity prices far beyond any reasonable valuation, leading invariably to an eventual collapse of the bubble.